Material Vision — Silent Reading

(2014-2015) University of Tromsø, Nordic Music Days, Trykkeriet

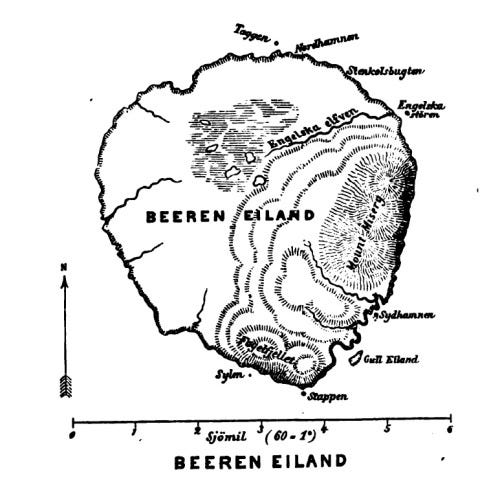

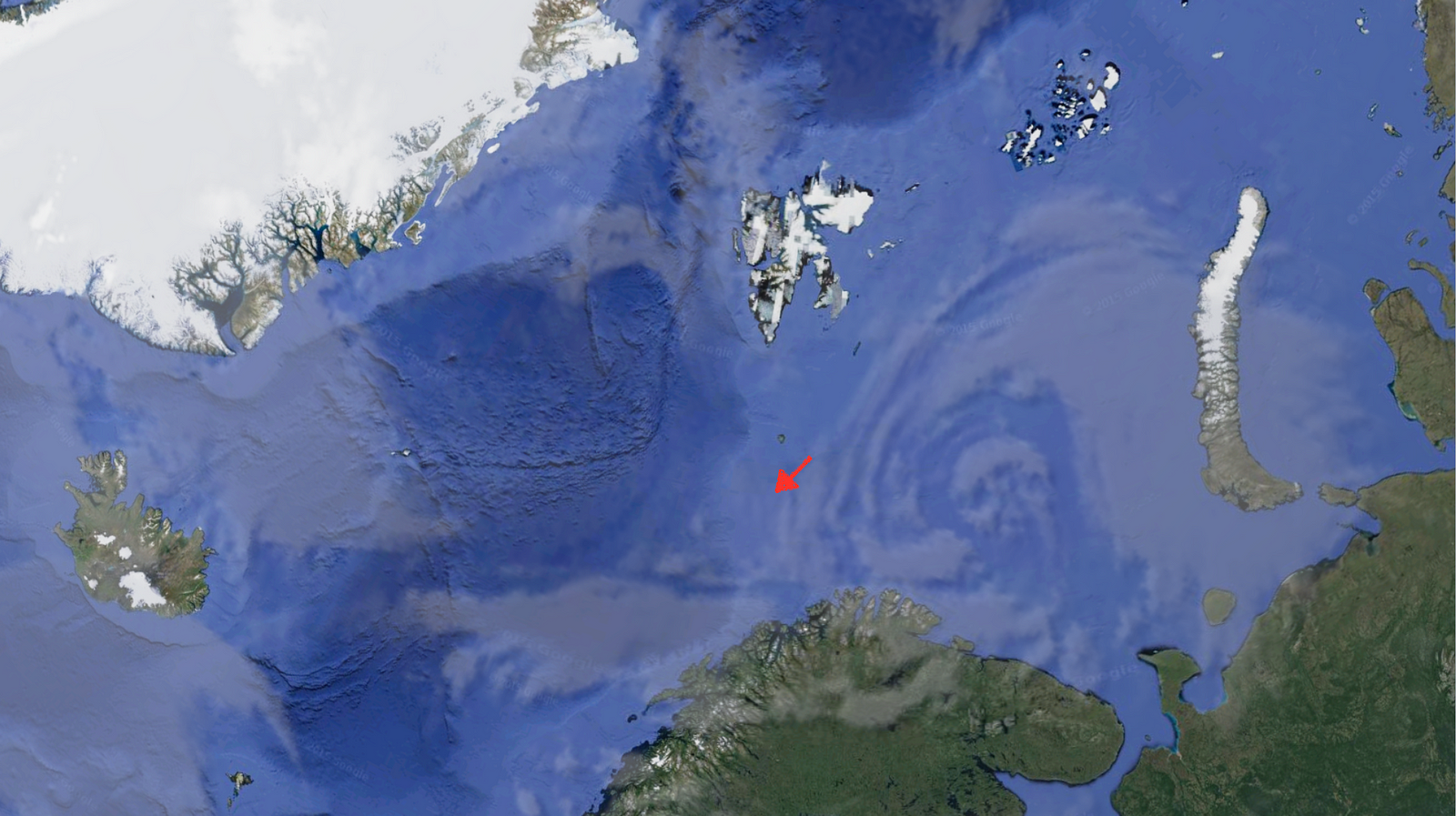

Bear Island (Bjørnøya in Norwegian), was originally named Beeren Eiland by Dutch explorer Willem Barents in 1596, after being attacked by a polar bear on its shore. Later Norwegian geologist Balthazar Keilhau would describe the island as the “Cadaver of the Earth” due to its complete lack of vegetation and harsh weather conditions.

This journey starts in the archives of the National Polar Institute of Norway, located in Tromsø in the northern part of Norway. Sifting through the thousands of scientific photographs I was looking for examples of a particular landscape, or rather a particular way that a landscape affects my eyes. Soon some stood out, photographs from the tiny and fairly insignificant Bear Island, taken during geology and geography expeditions at the beginning of the 20th century.

The photographs I found myself drawn towards, had a certain pre-modernist look, similar to more well know scientific photographs from late 19th century expeditions in North America by Timothy H. O’Sullivan and his peers. For my project I was looking for a landscape devoid of obvious points of attention — landscapes that to a large degree is reduced to optical categories, a space made up of pure lines and deep perspective. These landscapes also inherits a sense of otherness, and a sense of being uninhabitable and desolate — landscapes where only people of great experience and knowledge (e.g. Scientists) can endeavor to venture. The photographs of this pioneering era were partly given the disorienting look precisely for this reason. In order to obtain funding for further expeditions, the scientists deliberately exhibited nature as a foreign, incomprehensible and difficult place, ready to be conquered by science.

In exploring a unfamiliar landscape, one cannot avoid a certain process of appropriation, whether one is exploring for the purpose of politics, resources, science or art. It seems like the explorer’s gaze cannot help but desire to possess and master the object in view. And this in turn bleeds into the aesthetics of how it is represented.

Back to the archive photos, this time using an eye-tracker to draw a line following the movement of my eyes. In this case I registered the first impressions, about 2 seconds per image. The lines drawn on these images are done by the eye-tracking setup. For the work on archive material I sat down in front of a screen showing the pictures one by one and the tracker read the minute movements of my eyes. This is a good way to observe how the eyes quickly orient themselves and make sense of a landscape.

The next step was to go there in person, to Bear Island, and do my readings in the field. Questions I was pondering: How would being there affect the mental disposition, and the function of the senses? How does staying for a prolonged time in a landscape, tuning into it, change the way we view it? Needless to say it is not the easiest place to reach. A permanent meteorological station is the only inhabited place, with about 6 people on duty for half-year deployments. I joined a Nordic expedition of science historians, with a plan to walk in the footsteps of some early pioneers of polar science. We arrived mid-July, dropped off by a patrolling coastal guard ship. The next two weeks we spent crisscrossing the island on foot, sleeping in old hunters cabins that are being kept up by the friendly staff of the meteorological station. At each place I installed my instrument and did a series of experiments.

The eyes have two basic motions, saccades and fixations, the saccades are rapid shifts from one area to another, and the resting in one spot is a fixation. In reading a text for instance the eyes have about 5 fixations per line (or one per 7–9 characters). This is because only the center of the field of vision gives detail enough for reading text. The tuning instrument I constructed has hammers that hit the tuning forks in various patterns. They are triggered by the fixations of my eyes, and the position of my gaze in the landscape chooses which forks are hit, and pitches played. This becomes a very peculiar experience for the subject using the equipment, as the audio from the instrument is somehow connected to the object you are viewing, so that glancing around gives a certain sound to each thing you are looking at. You are hearing the eyes, but also hearing the objects and the landscape. The instruments become a learning tool where the landscape itself teaches the method of how it should be seen.

Naturally your disposition affects the movement. Being a musician and composer I instantly start composing music by rhythmically moving my gaze from place to place, back and forth, creating patterns. So I find myself somehow in between complete awareness of my eyes’ movement, and on the other side aiming for a free gaze — letting the instincts control the movement automatically while looking. The different states of consciousness and intentionality merge and become inseparable. A free gaze upon these landscapes so invested in politics, art and science at times seems impossible.

The ground on Bear Island is mostly mud that melts during summer and becomes a prehistoric soup, the other half is a rocky terrain that become like a labyrinth if you lose your way. The highest mountain, Mount Misery, has vast amounts of fossils pouring down its pyramid like sides, from a time when the island was still at the bottom of the sea. The lakes on Bear Island are extremely toxic from precipitation that collect all environmental toxins from Europe and drop them over this island because of the weather systems. All around there are dead birds scattered after a diet of fish from these lakes. Luckily (or unluckily depending on your point of view) there are rarely polar bears there nowadays because the seas north of the island doesn’t freeze over in winter as it used to. Still you should always bring a gun.

I found out a bit too late in the planning that it is also called the island of fog. During summer there is thick fog around 20 days of the month. I was starting to think, maybe not the best place for an eye-tracking project.

In 1883, M. Lamare was the first to use a mechanical eye-tracker, by placing a blunt needle on the participant’s upper eyelid. The needle picked up the sound produced by each saccade and transmitted it as a faint clicking to the experimenter’s ear through an amplifying membrane and a rubber tube. The rationale behind this device was that saccades are easier to perceive and register aurally than visually. The first system that didn´t have to be physically fastened to the eye, was built by Guy Thomas Buswell in Chicago in the 1920s, using lightbeams reflected off the eye. Today computerized systems are used to help disabilities, measure reading and the effectivity of commercials. Needless to say, it is not usual to bring this equipment out in the field. It is normally done in a highly controlled laboratory context. A lot of preparation was needed to make sure everything would work under various outdoor conditions. When it was not possible to bring the whole instrument rig, I would just record my eye movements with a smaller mobile camera with an app that also could play sounds to give the audible feedback.

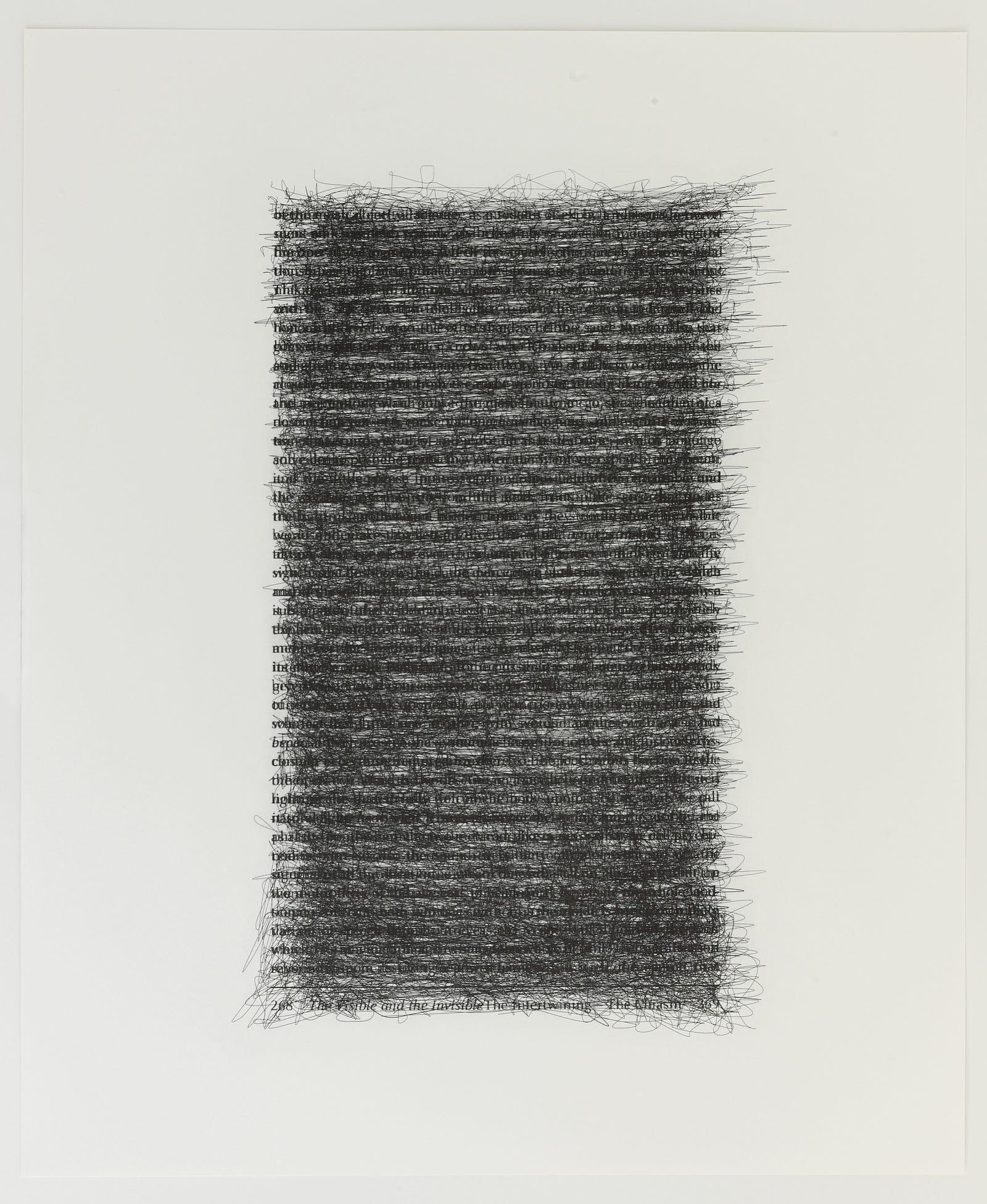

Reading as activity is so widespread and taken for granted in gaining knowledge today, that it might be difficult to see that it too has changed over time, that there is a history of reading. Up to the medieval ages reading was tied to the voice, by the fact that all texts should be read aloud — recited, even in solitude (or so-called reading rooms that any roman villa worth anything should have). The texts also showed this fact, but not having any spaces between words and no additional signs, because they were only meant for oral reading. The development of other diacritic and punctuation marks came later, parallel to the development of the earliest scores for music. The transition to silent reading (famously described by Augustin as the munk Ambroses invention), also resulted in the invention of new reading techniques. The gaze started moving in new saccades, the speed of reading increased and reading directly without preparing became possible. The text became released from the author and the presence of the voice, and became a format with its own inherent creativity.

[In order to] be able to see sublimity in the ocean, regarding it, as the poets do, according to what the impression upon the eye reveals [ger. augenschein], as, let us say, in its calm a clear mirror of water bounded only by the heavens, or, be it disturbed, as threatening to overwhelm and engulf everything.

- Kant, Ciritique of Judgement, ak. 270

In philosophical aesthetics Kants concept of the sublime is central, and it is especially connected to experience of different landscapes of nature, typically when something becomes very “big” or overwhelms us with its “power”. But Kant is not a romantic, and the quote above is one of the most cryptic in his aesthetic work. What is seeing “as the poets do”? What does augenschein mean (“the impression upon the eye”)? The sublime ends up being a pure formal reduction to geometric and optical categories, and this in sharp contrast to what Kant himself aimed for by introducing the aesthetic experience (for more moral or political aims). The formalism becomes so extreme that the shapes no longer harmonize with each other, and loose any connection to concepts or goals.

This “impression upon the eye” becomes in the theory of philosopher Paul de Man the starting point for re-interpretation of the sublime as such an amputating and fragmentizing experience. A kind of experience he calls “material vision”.

The artwork that resulted from this expedition, was commissioned by the University of Tromsø, and their new faculty of technology building. In addition to the video shown here, I also made 6 photogravure prints based on various image material and eyetracking registrations. The first two was based on the archive material from the polar institute. The next 3 my own medium format photographs from the island with eye-tracking.

and finally one highlighting reading of an 30 page article with eyetracking.

The photogravure process transfers the images to etched copper plates and is printed as intaglio print. The eye-tracking on separate plates are then imprinted onto the image. This complex and rare printing process brings out the physical aspect of the landscape hitting the eye and the eye scratching its mark into the view.

Bear Island might be a cadaver, but it is actually a corpse teeming with life. This island belongs to the birds. They flock to different areas of the island, but especially its southern cliffs. Bear Island has the largest colony of seabirds in the Northern hemisphere. At least a million pairs find their home there during the mating season. And the rest of the island is also full of them. When I wanted to do long more meditative eye-trackings to see what happened to my perception over time I was constantly being attacked by birds swooping down to chase me away.

Time moves to a standstill in the freezing climate. There are very few bacteria and fungus to break down organic material. So what you leave behind is stored in the time capsule that is the Arctic. We could eat food that should be long rotten, and we could find garbage from previous expeditions years ago still lying around.

There really should be no man on this island.